With the Winnett Specialist Group Psychologist, Georgie Beames.

When it comes to discussing obesity with patients in General Practice, time constraints, a lack of effective options, and finding the right language are important concerns. These challenges are often compounded by concurrent mental health issues, as highlighted in a study by the RACGP in regional Victoria.

Comments from GPs included:

“It is an enormous mental health issue… it’s what is going on here in the mind that is the most important bit.”

“If somebody is a bit, um, fragile, you certainly wouldn’t be bringing up their weight.”

Whilst weight loss injections and surgery remain increasingly popular options, more and more patients are also including mindfulness in their arsenal in the war on weight – and a recent report in Nature 2024, finds that mindfulness meditation modulates stress-eating and its neural correlates.

This report, which investigated the effects of mindfulness on stress-eating behaviour, involved overweight individuals participating in either a 31-day web-based mindfulness mediation training or health training.

Behavioural and resting state fMRI data were acquired before and after, and mindfulness meditation, in comparison to health training, was found to both increase mindfulness AND reduce emotional eating.

“These behavioural changes were accompanied by functional connectivity changes between the hypothalamus, reward regions…in addition to changes observed between the insula and somatosensory areas,” the study found.

Earlier studies vindicate these findings.

A 2018 meta-analysis in Obesity Review found that the practice may be a “moderately effective tool” in reducing obesity related behaviours.

The British Journal of General Practice also agrees mindfulness should not be underestimated as a mainstream medical intervention, while the Journal of The American Medical Association, suggested way back in 1999 that doctors should integrate mindfulness techniques into their own self-care – to be able to provide optimal care to their patients.

“Mindfulness informs all types of professionally relevant knowledge, including propositional facts, personal experiences, processes, and know-how, each of which may be tacit or explicit,” it found.

“This critical self-reflection enables physicians to listen attentively to patients’ distress, recognise their own errors, refine their technical skills, make evidence-based decisions, and clarify their values so that they can act with compassion, technical competence, presence, and insight.”

With this in mind, here are some of my top strategies for GPs to discuss with their patients recovering from bariatric surgery – when the brain’s hunger drivers have been dampened, allowing them better control over their food cravings.

Make mindfulness a habit

To eat mindfully, encourage patients to eat deliberately, non-judgementally, and with full attention – not in front of a TV or screen. Encourage family mealtimes, and advise against eating while on the phone, standing up, or moving around.

Encourage patients to savour their senses

It is important to encourage patients to use all their senses when eating; to savour the colours, tastes, aromas, textures, and sounds of the meal.

Also, encourage patients to identify the ingredients in the food they are tasting, or how the food feels. Does it dissolve on the tongue? Does chewing make a sound? Is it sticky, crunchy, or smooth? How warm or cold does it feel? What colour is the food?

Remember the 20 chews rule

Encourage patients to chew each bite 20 times, savour each bite, and put down the fork between bites. This gives them time to think about how full they are.

Listen to the hunger signals

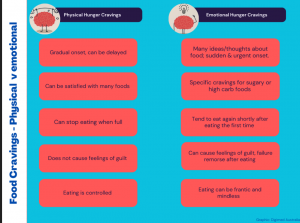

It’s important for patients to be mindful and highly attuned to the differences between physical hunger cravings and emotional hunger cravings.

Physical hunger cravings develop slowly and can be delayed, whereas emotional hunger cravings are sudden, urgent, and thoughts of food become all consuming.

Physical hunger can be satisfied with a variety of foods, while emotional hunger tends to focus on high-carb, high-fat, and sugary foods. Emotional hunger often leads to guilt after eating, which doesn’t happen with physical hunger.

With physical hunger, it’s quite easy to stop eating when full, but emotional eating often leads to eating again shortly after.

Use a food diary or app to track what you’ve eaten

Encourage patients to use a food tracking app or keep a diary. Making a list and sticking to it, or using an online order, helps avoid impulse buys. Suggest filling most of the cart in the produce section and avoiding the centre aisles, which are usually stocked with processed foods. Out of sight, out of mind!

About Georgie Beames

Georgie Beames is a Melbourne psychologist with a core interest in emotional eating and weight loss. She incorporates somatic stimulation techniques, mindfulness techniques, cognitive therapy, and EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing) in her treatment of weight loss.

If you have any questions or need support, you can book an appointment with Georgie through the Winnett Specialist Group by contacting us here or calling at (03) 9417 1555. Our team is ready to support you through every phase of your journey.

Georgie Beames

Psychologist